The World’s Tax Collectors Agree Terms of a Cartel

They’ve finally done it, almost. The tax collectors of the G7 industrialized nations, assembled in London this past weekend, have agreed that they need more money, some to pay for the damage done by Covid, in President Biden’s case to pay for the transformation of America into a European-style welfare state, which means he needs lots of money to finance child care, family leave, higher pay for selected groups, free education for toddlers and high school graduates. Somewhere in the neighborhood of $6 trillion, some $2 trillion more than in the normal, pre-pandemic year 2019, and the largest claim on the nation’s income and wealth since World War II.

That creates a problem in a globalized world in which the geese he wants to pluck can take flight from these shores and alight in countries that place fewer demands on the revenues and profits of international businesses. That sort of reaction to the tax burdens Biden has in mind also means jobs disappearing over the horizon, factories being built in countries for the benefit of populations that cannot vote to re-elect Democrats. Yes, the government can add to the already-mountainous pile of its IOUs, but surely not without limit.

The world’s tax collectors have watched helplessly as their governments’ insatiable desire to expand their reach have been thwarted by the ability of the world’s international companies to shift profits to countries with the most benign tax environments.

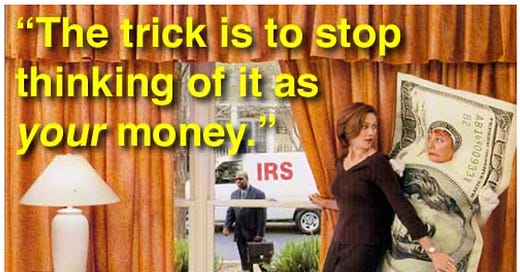

Enthusiasts for ending this situation use revealing language. The Economist calls for an end to “Corporate- Tax Dodging….End the Contortions… .” And reports, “Around the world exchequers are robbed of up to $240 billion a year by firms rerouting profits, the OECD reckons.” “Robbed” is not the word I would use. It suggests the revenues and profits are the rightful property of the tax collectors and their political masters, rather than the companies and workers who generated that income. This naughtiness, although perfectly legal, must be stopped. “Time for new rules …. [to] avoid chaos” conclude the magazine’s editors. Some might substitute “competition” for “chaos”.

Negotiations and More Negotiations

The G7 finance ministers agreed to the first forward step since 2013 on the long road to setting a floor under the tax rates to be charged international companies, and getting their hands on the profits of America’s digital giants. These governments have watched jealously and hungrily as low-tax Ireland – a 12.5% corporate rate compared with 29.9% in Germany, 28.4% in France – has attracted jobs and investment resulting in GDP per capita of $78,779 compared with $46,468, $42,329, $40,496 and $33,226 for Germany, the UK, France and Italy, respectively. That’s what a growth rate 140% of the EU average between 1986 and 2006 can do for a country.

Negotiations between the US and its G7 colleagues, and with the OECD (137 members) have staggered along since about 2013. When European countries went ahead with their plans to tax America’s digital giants, President Trump responded with tariffs on the goods they are peddling in America. He undoubtedly was influenced by his close study of American history, which includes rebellion against the tyranny of taxation without representation. A new President, surrounded by a team with mixed views on the role to be accorded American history, a new belief in international cooperation, new plans to wring more tax money from international companies among other geese.

Getting At Big (American) Tech

Start with America’s big, successful technology companies, of which Europe has none or, being charitable, few. The UK and five other countries are threatening to impose a digital tax, which prompted Trump to impose retaliatory tariffs. In the new era of fraternal tax policies, the Europeans have agreed to suspend their tax and Biden to suspend application of the tariffs. The decidedly unfraternal bickering will be replaced with a system that will force the largest multinationals with profit margins of at least 10% to allocate “at least 20%” of their global profits to countries in which they make their sales, even if they have no physical presence in the countries in which they record those sales. A major concession by the Biden team. The definition of the largest global companies is not yet agreed, but Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen says “by almost any definition” it will snare the likes of Amazon and Facebook. Those geese, their evader teams probably already at work, profess to see this assault as a good thing, bringing “stability to the international tax system” (Amazon), and “a first step towards certainty,” according to Facebook Global Affairs VP Nick Clegg.

Ending “A Race To The Bottom”

In return, the partners-in-taxation agreed to shackle footloose tax minimizers with a minimum global corporate tax rate of at least 15%, closing an escape hatch for companies that now pay no or little tax in the U.S., to Biden’s annoyance. If a company avails itself of Ireland’s low 12.5% rate, other countries agree to add a rate of 2.5% to bring it up to the new global minimum of 15%. Whether this will prompt Ireland to veto the deal, which needs unanimous approval, is not known, although it has expressed unhappiness. Its finance minister, Paschal Donohoe, estimates that it could result in an annual revenue loss of €2 billion ($2.4 billion), equal to one-fifth of the nation’s overall tax revenue, and promises to “continue to make the case for legitimate tax competition within certain boundaries and for the role of small and medium sized economies in the agreement that is yet to come.” The early unfurling of a seeming surrender that will appease the taxpersons is italicized for the convenience of the reader.

Joy Unrestrained

The happiness of the tax collectors was variously expressed. According to The Financial Times:

· Olaf Scholz, Germany: “very good news for tax justice and solidarity.”

· Mario Draghi, Italy: “a historic step towards a fairer and more equitable society for our citizens.”

· Bruno Le Maire, France: “a fair taxation of digital giants … [we have] “risen to the challenge of this historical moment.” France will fight for a higher minimum in coming months.

· Janet Yellen, U.S.: “a revival of multilateralism, a willingness of leading nations …to address the most critical challenges facing the global economies.”

· Rishi Sunak, UK: “a historic agreement on global tax reform…. [that will] level the playing field.”

The Long Road Ahead

Sunak, who chaired the conclave and attributed part of its success to the fact that it was a face-to-face meeting, announced, “We are confident it will create the momentum necessary to reach a global agreement.” The next step will be taken at the G7 June11-13 heads of state meeting in Carbis Bay, Cornwall, to which leaders from Australia, India, South Korea and EU have been invited. “The perfect location for such a crucial summit”, enthuses host Boris Johnson.

There remain procedural hoops through which the parties must jump, including approval by the 137 nation OECD at its June 30-July 1 meeting in Venice and another finance ministers’ gathering the following week, out of which should come what departing OECD secretary general Angel Gurria calls “the outline of deal”, followed by “a final package” to be developed by G20 ministers at a meeting in Rome on October 29-31. Then comes a two-year process of drafting enabling legislation and treaties, which must obviously be preceded by a period of intense salesmanship by each nation’s politicians and, in the case of any treaties in which the U.S. is involved, a two-thirds vote of the Senate. Heisting billions from the world’s taxpayers is a tedious process.

The Brave New World Of Inescapable Taxes

At which point we will have an international tax regime in which America will allow foreigners to tax American companies, without tariff retaliation, in return for an agreement from other countries to a minimum tax rate that allows Biden to proceed with the construction of a European-style, expansive welfare state in America. The benefits, says Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, will be “tremendous… The race to the bottom … is going to stop.”

Those benefits are clear to the tax collectors, but less obvious to businesses that will lose the benefits of international competition for their investments, and consumers and workers who will pick up the bill for the higher costs imposed on those businesses.

So Who Won The Game of Hide The Profits?

The taxmen may feel they have won, that their coffers will overflow with the previously ill-gotten gains of the evaders. They might think again. Diana Furchtgott-Gott Roth, a former treasury department official now ensconced at George Washington University, points out in a paper the tax collectors would do well to ponder, “The tax burden is made up of more than tax rates. Exemptions, deductions, depreciation schedules, and special incentive packages can all be tweaked to compete.” And, as Ireland’s Donohoe points out, the longevity of foreign investment in his English-speaking country, the stability of the regulatory and tax regime, the favorable time zone, all give him comfort as he negotiates with the collectors. He has not mentioned a possible appeal to President Biden, whose love and concern for Ireland’s well-being is unbounded. He attributes his sense of humor, his temper, black moods, the chip on his shoulder to his Irish inheritance which, notes The Washington Post, “he uses to frame his personal story and political identity.”

The tax-fixing cartelists manqué will find cheating more than a mild annoyance, the skill of private-sector lawyers, accountants, lobbyists undiminished. Not a bad thing: new problems, new reasons for emission-generating gatherings in the world’s garden spots.